Collatz-Intro - Approximations of log(3)/log(2): Some illustrative graphs |

Workshop |

|

|

In the following I present some graphs, which illustrate a known critical condition, which serves for primitive loops (or "1-cycles") as well as for the "waring-problem". The condition is given as |

|

Let x = 3^N/2^N be displayed as a irregular fraction base a power of 2: let q = 2^N and d be the integer

d=floor(x/q) then let x be represented as x = d * q + r which means, that in the numbersystem base(q) the both digits d and r make x x = "d r" (digits d,r base(q)) The critical condition for a 1-cycle (as well for the waring-inequality) is then d + r < q because it is needed, that by division by q-1 no carry occurs in x "d r" "d r" "d r" = " d d.d d d d ..." + " r.r r r r r..." = " d d.d d d

d ..." and x - 1 " d d.d d d d ..."

Now the critical condition for a primitive loop says, that the result must a) be integer b) a power of 2 to make a primitive loop possible since 3^N - 1 x - 1 In the base q-system this means: e 0 0 = " d d.d d d d ..." Since d is always smaller than e, one can immediately see, that it must be e-1; also each digit of the rhs-sum must produce a carry , and the new resulting digit must precisely 0. So this means, to have a promitive loop, it needs, that d+r = q or a multiple d+r = i*q. Therefor it is a most interesting question, whether d + r < q holds for the given rhs-term for all N. If this statement could be proven for the interesting values of x and q, then the primitive loop is disproven as well as the "waring-problem is completely solved" (see [mathworld/waringproblem] and mathworld/powerfrac ) . The same problem was attacked by Kurt Mahler, who analyzed that question systematically and formulated a criterion called Z-numbers. If there were no Z-numbers, then this would be equivalent to the proof of the critical condition. Mahler didn't succeed in proving the nonexistence of such Z-numbers, but could at least state, that at most finitely many such numbers exist. (see [mathworld/Z-Numbers]) |

|

Below the graphs, which may illustrate that problem. |

|

Legend: Data x = 3^N/2^N are shown in a two-dimensional table, where the y-coordinate is d and the x-coordinate is r. If the sum of d+r < q for all interesting x then this means, that all entries are below the main diagonal. Normally one would expect, that the value of r is randomly and uniformly distributed and independend of d. But there are also exceptions, as it seems with the combination of x = 3^N/2^N. In the following I show also some variations of the problem, where instead of basis=3 some other bases=b in the range 2 < b < 4 were taken to illustrate specific variations of the problem. In the following graphs the areas of higher N were mapped into the same table by rescaling. So the points of the scatter must indicate the power N; I used a bigger size for lower N and smaller size for higher N. |

|

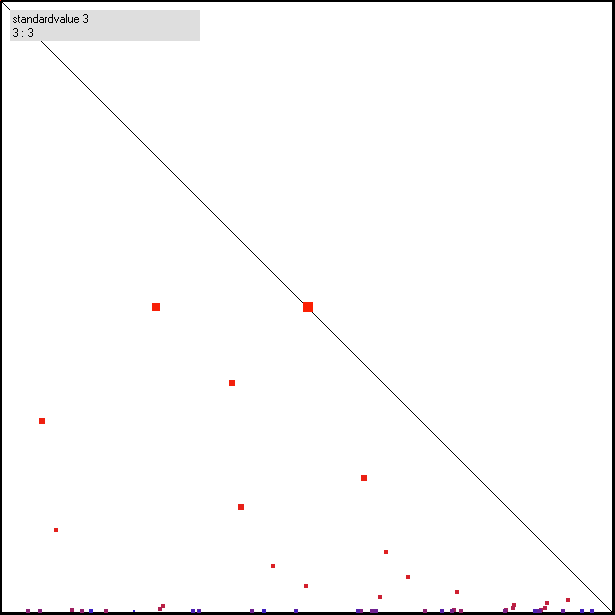

Fig. 1: an arbitrary base b other than 3 exhibits an expected random-scatter on the x-axis (=r), independent from the y-value (=d). In this case I took log(64)/log(3), since it is a special pretty case for this claim :

One can see, that no obvious relation is between the y and x-values; that means for each d there is an arbitrary r in x/q = d + r/q with x = b^N and q = 2^N |

|

Fig. 2: the picture for b=3 exhibits, that the sum of d+ r is always smaller than q, or r< q-d:

This picture means, that empirically the condition holds above N=1 up to N=64 ( ;-) a *small* value indeed) and it easily could be, that even that restriction could be formulated sharper, as we see, that always a certain distance remains to the diagonal, where the best approximations may hyperbolic or logarithmic decrease with a function of N. |

|

Since the condition d + r < q steming from the Collatz-loop-discussion was identically formulated in the analysis of the Waring-problem, but is unproven yet, it is of interest to see how variations of the problem behave. From an analysis (not finished yet) of the approximation-ratio as a function of N there is a strong indication, that this problem may be related to the properties of the number phi (golden ratio : phi - 1 = 1/phi or phi = (1+sqrt(5))/2 ), and phi could play a role as a certain critical value in that approximation, as a "norm" it may behave like a zero-element. Indeed we see a beautiful coincidence between m and p in the table for phi: |

|

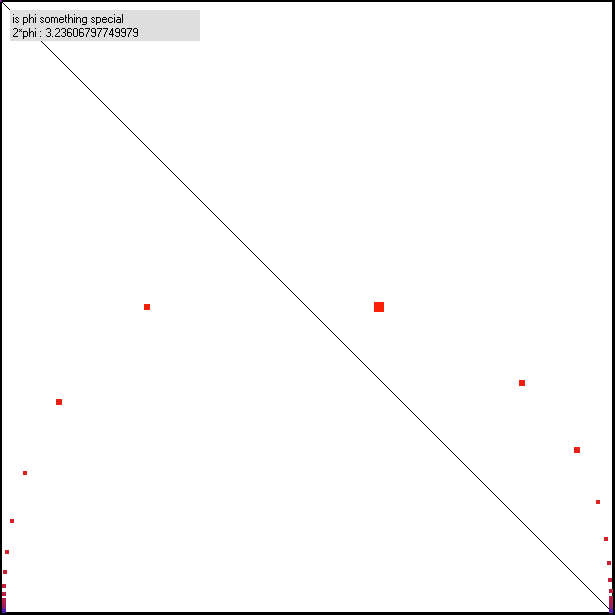

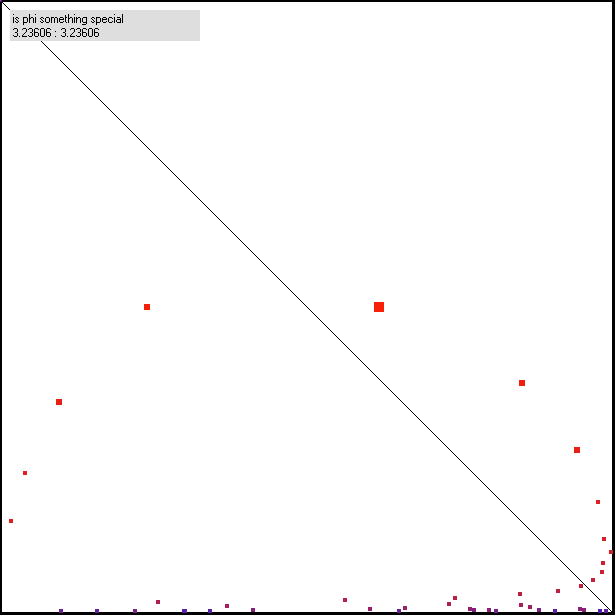

Fig. 3: the picture for b=2*phi exhibits, that phi certainly plays a special role in the approximation-analysis:

This is a very remarkable illustration, since here we do not need approximation-estimations. Every 2'nd value N exhibits either the smallest or the highest residue of a class, something like d + r = c/N like an exact value, depending on N. Clearly this comes from the property of phi, that phi^2 = phi^1 + 1 which means, that the fractional part of phi^2 and phi is the same. This basis phi is the only case I can imagine, where the possibility of determining a function for the quality of an approximation depending on N seems given- in all other cases that function would be stepwise or somehow else erratic, with good and bad approximations for increasing N - and only a general bound for the intermediate best approximations may be accessible as a function on N, like the one, that is formulated by the waring-condition |

|

Now take phi as a kind of norm-value. What does happen, if we slightly change this value? |

|

Fig. 4: here phi was modified by simply cutting digits to 1e-6:

One can see, that for higher values N this modification comes into play, but still a certain regularity remains at the beginning |

|

Fig. 5: another slightly distortion of the value of phi

The generally expected "randomness" for r (=x-coordinate) occurs from higher N. |

|

In the following some randomly chosen values around the interesting base 3: |

|

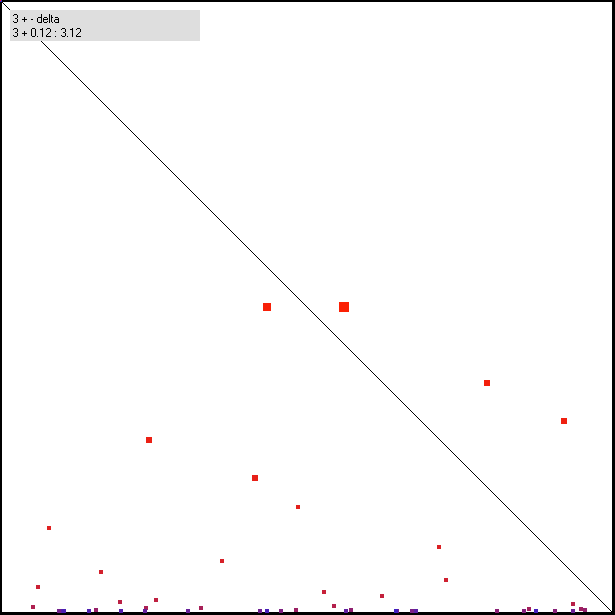

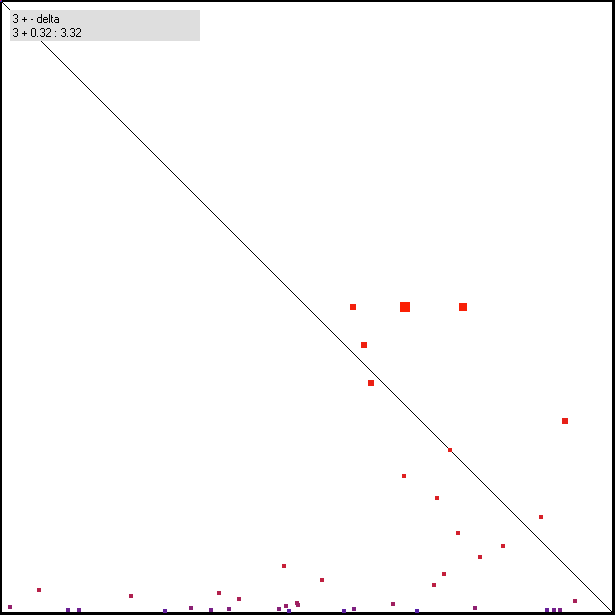

Fig. 6: some deltas added to 3

The d + r < q condition is already spoiled, at least for small values of N. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Another interesting question is, whether some other known constants do show a typical regularity, from where approximation-rules could be derived. The 2-log of e has an impressive pattern: |

|

Fig. 7:

This number seems to have the same property as the basis 3, and even it seems to have a better regularity in the pattern as well as a greater distance to the d+r < q - diagonal. |

|

Variations over PI |

|

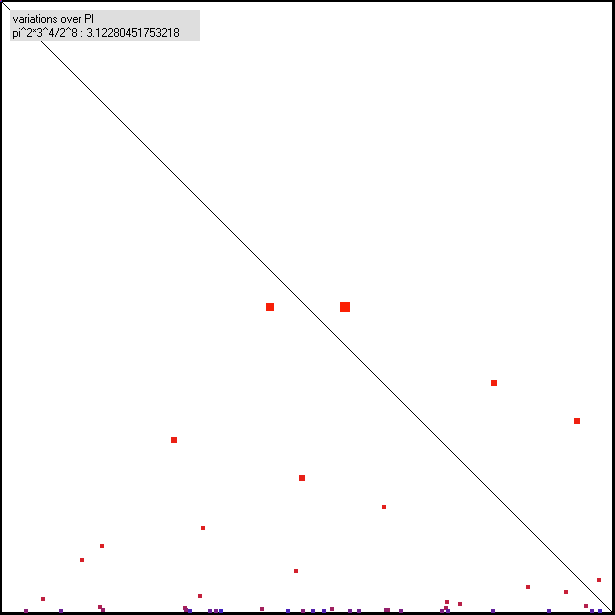

Fig. 8.1-1: Variations on pi^2

This number seems to have a hyperbolic characteristic. This value seems to satisfy that d + r < q very good, much more than the 3^N/2^N case, which is relevant for the loop-problem of the Collatz-transformation. |

|

Fig. 8.1-2:

This one not. |

|

Fig. 8.1-3:

But this one again. |

|

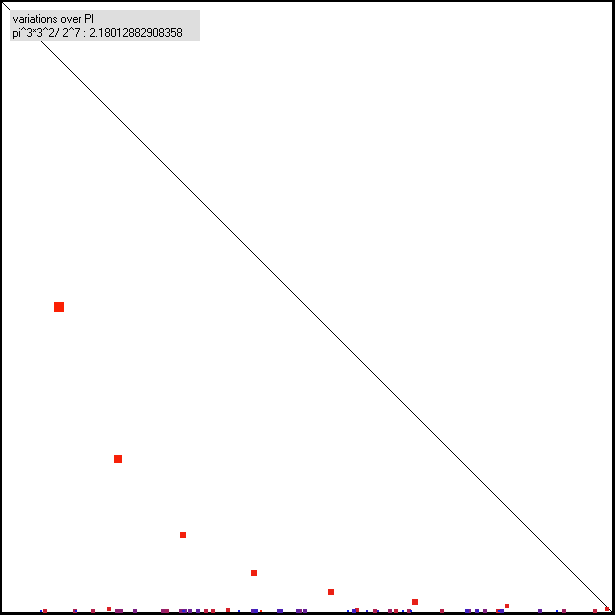

Fig. 8.2: Some variations about pi^3

This number seems to have a hyperbolic characteristic as well, but near approximations seem to occur with higerh values of m (see red dot in the right below corner). Fig. 8.2-2: Some variations about pi^3

Only some combinations of base b=(pi^A/2^B) show this hyperbolic behave. Here is d +r < q , and much more extreme than in the original base b=3 (=3^N/2^N)-matter |

|

Fig. 8.3-1: Even some powers show exotic behave

Only some combinations of b=(p^A/2^B) show this hyperbolic behave. Again, that may be a candidate for further investigation of its behave regarding d + r < q, which seems even more clear than in that original one with b=3 ( 3^N/2^N- problem) . |

|

It may be, that if one takes bases differing from b=3 (as in the collatz-problem) like the ones, which were shown here, one could make similar observations (or completely different) to that of the 3x+1-problem, especially in regard to the question of loops. Currently I am investigating the approximation-behavior of the 3^N/2^N-problem, and may be from that an argument for further restrictions for a N-dependent-formula for that approximation-quality can be found, which empirically seems much higher than the waring/primitive-loop-criterion, thus denying the primitive loop on a much higher level. (My current best guess for the highest low-bound is something of this function of N

which I estimated from numerical and graphical display for values up to some N~10^40.) |

Gottfried Helms

27.8.2004