This page contains automatically translated content.

Intuitive misconceptions about evolution: these teaching methods help

Image: Tim Hartelt.

Image: Tim Hartelt. Image: Tim Hartelt.

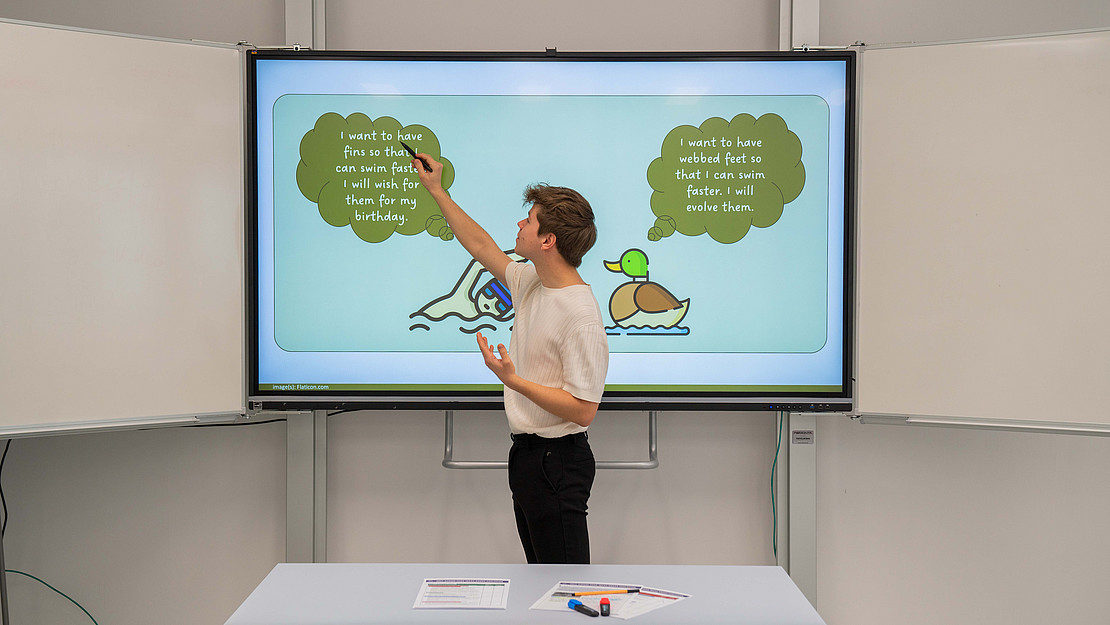

Image: Tim Hartelt."The giraffe grew a long neck to reach the tall leaves." "Ducks developed webbed feet because they wanted to swim faster." Most pupils have such non-scientific, intuitive ideas about evolution. These ideas are intuitive and frequently used because we often act purposefully and deliberately in our everyday lives and therefore intuitively assume that evolution is also purposeful and deliberate. Certain teaching approaches can help to reduce these intuitive ideas about evolution - if they explicitly address the misconceptions instead of just teaching scientific counter-concepts.

"Our results show how important it is not only to teach scientific concepts in class, but also to take intuitive everyday thinking into account. If the students' intuitive ideas are addressed and reflected upon, they are even more likely to develop scientific ideas than if only scientific concepts are taught," says Tim Hartelt, who conducted the study together with Professor Dr. Helge Martens, Head of the Department of Biology Education at the university.

The two scientists tested two methods at over 30 schools with a total of 730 pupils, which were intended to make pupils aware of their intuitive thinking and enable them to regulate it in the context of evolution:

In the first experimental setting, all pupils in a class were first asked to explain in writing how the ability to run fast evolved in cheetahs.

One half of the class received additional information on three common misconceptions about evolution (for example: "Evolution is purposeful and follows a plan"). The group was then asked to examine their own explanations for the three misconceptions and mark them in color.

As a control group, the second half of the class received no information about the intuitive fallacies, but only a list of technical information about evolution.

The first group, who received information about the widespread misconceptions and checked their own results against them, showed a much higher use of scientific evolutionary ideas in a later test than the second group, who were only confronted with the scientifically correct information.

In the second setting, the students first learned about various intuitive fallacies. In subsequent units, different contexts (everyday life, science, social issues) were examined with the pupils in order to test whether intuitive conclusions can be helpful or counterproductive in these areas. Here too, in contrast to a control group, the pupils taught in this way later showed a higher use of scientific ideas and a lower use of intuitive ideas when explaining evolution and an increased awareness of their thought processes and intuitive thinking.

The full study was published in the Journal of Research in Science Teaching on March 28, 2024 and is available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21938

Contact:

Tim Hartelt

University of Kassel

Department of Didactics of Biology

Phone: +49 561 804-4363

Email: hartelt[at]uni-kassel[dot]de