This page contains automatically translated content.

Kasseler Biologen entdecken neues Protein, das Zellen stabilisiert

Image: University of Kassel

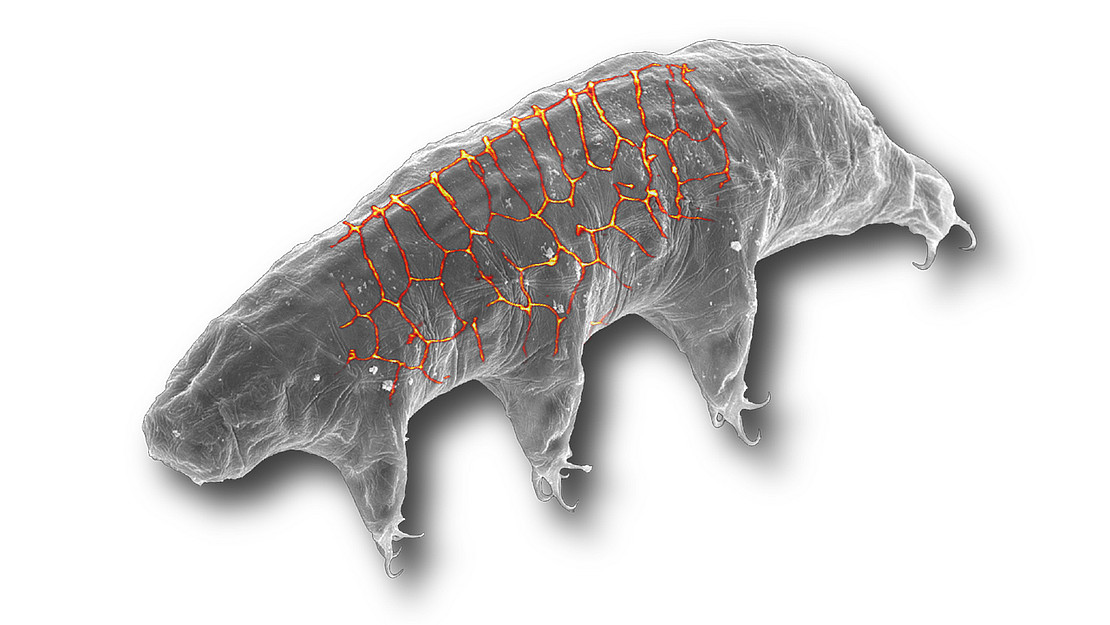

Image: University of KasselBärtierchen sind ein biologisches Phänomen: Viele Arten der weniger als einen Millimeter großen Lebewesen halten extreme Hitze ebenso aus wie hohe Strahlung oder Temperaturen von unter 20 Grad minus. Sie gehören zur großen Gruppe der sogenannten Bilateria (Zweiseitentiere), zu der auch Wirbeltiere und damit Menschen zählen. Aber anders als fast alle sonstigen Vertreter dieser Gruppe verfügen die Bärtierchen, die sowohl an Land als auch im Wasser vorkommen, nicht über bestimmte Proteine, Bausteine der sogenannten cytoplasmatischen Intermediärfilamente (cytoplasmatischen IFs); diese Proteine stabilisieren die Zellen der Zweiseitentiere durch gerüstartige Strukturen und machen sie so widerstandsfähiger. Den Bärtierchen (lateinisch Tardigrada) gingen diese Proteine im Laufe der Evolution verloren. Wie die Forschungsgruppe um Prof. Dr. Georg Mayer, Leiter des Fachgebiets Zoologie an der Universität Kassel, gemeinsam mit Leipziger Kollegen um Prof. Dr. Thomas Magin herausgefunden hat, ersetzen Bärtierchen diese Proteine jedoch durch ein anderes Protein.

Die Biologen analysierten für ihre Untersuchungen den kompletten Satz aktiver Gene einer Bärtierchen-Art, Hypsibius dujardini. Dabei fanden sie drei sogenannte Lamine, das sind Proteine, die alle Bilaterier gemeinsam haben, die jedoch üblicherweise im Zellkern sitzen und nicht im Cytoplasma. Eines davon war bislang von keiner anderen Tierart bekannt. Versehen mit einem Marker zeigte sich, dass sich das Protein wie ein Gürtel an der Innenseite der Zellmembran anlagert – allerdings nur bei Zellen der Haut, des Mundes oder anderer Zellen, die mechanischem Stress ausgesetzt sind, wie beispielsweise im Bereich der Krallen. Von Zelle zu Zelle bildet sich so eine Gitterstruktur, die das Gewebe stabilisiert. Die Wissenschaftler nannten dieses neu entdeckte Protein „Cytotardin“. Die Ergebnisse veröffentlichten sie jetzt im Forschungsjournal „eLife“.

„Wir können noch nicht mit Sicherheit sagen, ob das Cytotardin auch für die extreme Widerstandsfähigkeit der Bärtierchen gegenüber Hitze, Kälte und Strahlung verantwortlich ist, aber die Vermutung liegt nahe“, sagt Prof. Georg Mayer. „Sicher ist, dass die Natur hier einen Trick anwendet, der sich immer wieder auch bei anderen Tieren zeigt: Wenn eine bestimmte Ausstattung im Lauf der Evolution verlorengeht – hier die cytoplasmatischen IFs –, die Fähigkeit aber nach wie vor gefragt ist – hier die Zellstabilität –, funktioniert der Organismus andere Ausstattungsmerkmale um, um die Aufgabe zu erfüllen. Anders gesagt: Die Natur findet immer eine Lösung.“ Den Bärtierchen half hierbei, dass sie einen kurzen Lebenszyklus und damit eine hohe Substitutionsrate haben, sprich: es viele Gelegenheiten für Mutationen gibt.

Lars Hering, Jamal-Eddine Bouameur, Julian Reichelt, Thomas M. Magin, Georg Mayer: Novel origin of lamin-derived cytoplasmic intermediate filaments in tardigrades. eLife 2016;5:e11117.

Link zum Artikel: http://elifesciences.org/content/5/e11117v3

Bild eines Bärtierchens mit Visualisierung markierter Zellen unter:

http://www.uni-kassel.de/uni/fileadmin/datas/uni/presse/anhaenge/2015/Baertierchen.png

Bildunterschrift: „Eine rasterelektronenmikroskopische Aufnahme des Tardigraden Hypsibius dujardini, überlagert mit einer Aufnahme des fluoreszenzmarkierten Cytotardin, veranschaulicht die Verteilung des Proteins in der Haut des Tieres (nicht maßstabsgetreu).“ Bild: Irene Minich, Julian Reichelt, Vladimir Gross und Lars Hering.

Bild von Prof. Dr. Georg Mayer (Foto: privat) unter

http://www.uni-kassel.de/uni/fileadmin/datas/uni/presse/anhaenge/2015/Georg_Mayer1.jpg

Kontakt:

Prof. Dr. Georg Mayer

Universität Kassel

Fachgebiet Zoologie

Tel.: +49 (0)561 804-4805

E-Mail: georg.mayer@uni-kassel.de