This page contains automatically translated content.

An interview with political scientist Wolfgang Schroeder on the AfD's poll results, his role as a political advisor and the task facing civil society

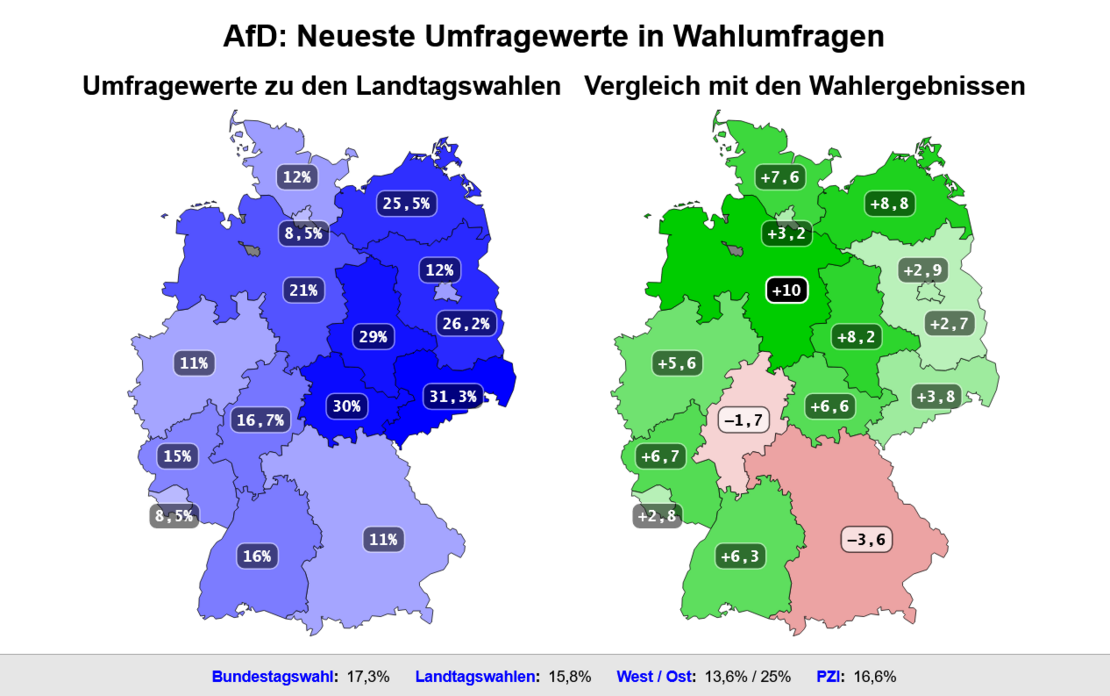

Image: dawum.de

Image: dawum.depublik: Mr. Schroeder, with the AfD, a party is approaching power that the Office for the Protection of the Constitution lists as a suspected right-wing extremist. Let's imagine for a moment that it comes into government, in a state or at federal level, and can rule unhindered. What would happen?

Wolfgang Schroeder: That would be tough. It would certainly try to change the framework in which we operate, similar to what we know from Hungary or Poland, for example. Firstly, the legal framework, for example in terms of how courts work or how judges are appointed; secondly, the AfD would certainly attack public broadcasting. In fact, it is already doing so, namely with motions in the state parliaments against "compulsory funding". And thirdly, one can imagine considerable interventions in education, science and culture, and not just in the area of language. In particular, the AfD would question the funding of cultural offerings or civil society projects against racism and misanthropy.

publik: You say that an AfD government would be "tough". Nevertheless, you are against banning the party.

Schroeder: I am not against a ban in principle. A democracy must be robust. But in view of the experience with the NPD ban, it is clear that this procedure is a ride on the razor's edge. That's why we should ask ourselves, firstly, whether more use should be made of the criminal code to prevent some activities. Secondly, there is the question of how successful a ban would be. The hurdles are rightly very high and the AfD is a very heterogeneous group. If such a procedure fails, it would be an AfD normalization programme. The party could present itself as the victim of an authoritarian state that is trying to eliminate unpleasant competitors from the field by judicial means. It would also relativize the commitment of civil society. So many people are campaigning against right-wing populism and for the basic democratic order. If the Constitutional Court were to certify that the party should not be banned, the question could be asked: Why are we actually doing all this? Because the protection of the constitution "from below" should not be thwarted by the protection of the constitution "from above". But there is another reason.

publik: Namely?

Schroeder: I think we have to live with the fact that 20 to 25 percent of the population is susceptible to right-wing populism, xenophobia and an authoritarian state. If the AfD were to be banned, another party would pick up the slack. I am a guest at the AfD party conferences, and you can already hear people talking about founding an "Alice Weidel movement". It is interesting that this seems to be a successful European model: right-wing parties with dominant female figures. One explanation for this is probably that this constellation relativizes the image of the masculine, thigh-slapping party without substantially changing the actual substantive ideological substance that is shaped by this attitude and interests.

publik: Are you at the party conferences?

Schroeder: Yes, accredited as a reporter for ZDF.

publik: What does that look like? How do they meet you there?

Schroeder: With cool professionalism. The party knows that it needs the attention of the media.

publik: If the party is not banned, then civil society will have to sort it out. In the first few months of the year, tens of thousands demonstrated against right-wing populism. Did that achieve anything? Or was it just the self-assurance of a left-wing bourgeoisie?

Schroeder : I was at demonstrations in Berlin, in Kassel and in my home region of the Eifel and I didn't get the impression that only the left-liberal milieu was out and about there. These rallies were a powerful moment. But of course it depends on a lasting commitment. It is now important to go to the associations, to go to the parties, to become active there, to help shape things and to take a stand. The parties may be doing things wrong in terms of what they offer and how they present themselves. But now would be the opportunity for young people to renew these exhausted parties!

publik: What do you think the other parties should do to counter the AfD?

Schroeder: Above all, they must do one thing: govern well. To do this, the players in the system need to become more responsive; helpless anti-fascism and simply marginalizing the right-wing populists will quickly reach its limits. I did not understand why, for example, distribution struggles as a result of increasing migration were not addressed for a long time. It seems clear to me that there would then be a counter-movement.

publik: Speaking of civil society, you recently gave input to the Catholic Bishops' Conference on the topic of right-wing populism. The bishops then publicly declared that the AfD was not electable for Christians. Did you expect that?

Schroeder: I was amazed. It's not often that political advice has such a direct impact. In this case, it had to do with the fact that the Catholic Church is on the defensive because of known problems. The bishops were able to demonstrate here, in addition to many internal church motives, that the church acts on a basis of values and is socially valuable.

publik: You are perceived as a strong voice in the media on issues such as right-wing populism, the AfD and the GDL strike. How do you assess the role of science communication as policy advice?

Schroeder : We scientists should definitely get involved. Even if it is usually a laborious process and politicians are very slow to react. In confusing times like these, society relies on science for guidance. Incidentally, in order to be able to provide advice, I find a position between basic research and practical application as well as an interdisciplinary exchange very helpful. The University of Kassel is characterized by both.

publik: You advise as an academic and are also a member of the SPD and the SPD Basic Values Commission - a conflict of interest?

Schroeder: It is sometimes a hindrance. Resentment against parties is widespread in the media - and in academia too, by the way. Yet our democracy thrives on party memberships and non-profit interest groups. As a scientist, I am independent and base my presentations and assessments on data and historically reconstructable developments. My approach corresponds to the concept of problem-oriented empirical research. I see the sometimes noticeable reservation of partiality as an attack on my professional ethos as a scientist who has been working empirically for forty years and who has conducted his own studies on almost all the issues on which he makes public statements. I see myself as an evidence-focused scientist. I use hypotheses and scientific methodology to arrive at results and make statements based on facts; whether they suit the SPD or other parties or not is not the yardstick. I do not look for arguments to support my desired statements. My normative position is based on the fundamental values of the liberal, social and democratic order.

publik: There is also a tense political climate at universities - mostly between small groups - whether it's about the war in Gaza, accusations of anti-Semitism or right-wing tendencies. What do you observe on campus in Kassel?

Schroeder : I perceive it differently in my seminars. Of course, the general climate in society is tense. But this is more noticeable among my students in the form of insecurity, sometimes also as a difficulty in concentrating. But discussions are conducted with tolerance for the other point of view. I remember that being tougher from my own student days. Maybe that's where civility comes in. You also have to realize that if 25% are open to right-wing populism, 75% are firmly on the side of our free and democratic basic order. I am quite optimistic: we should be able to deal with the current conflicts peacefully.

This article appeared in the university magazine publik 2024/2. Interview: Beate Hentschel and Sebastian Mense